|

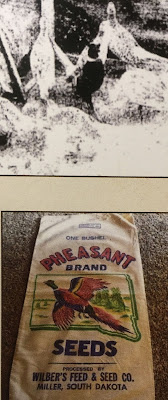

| Mary Yost (right) and her sister |

It all began in the early 1960s when Jack Seeman and his brother Jerry Yost wondered if they could raise pheasants in captivity. They decided to find out. But Jack moved out of state and Jerry's day job as a plumber kept him too busy to tend to the pheasants alone. Their mother, Mary Yost, helped out "for something to do" and "to keep busy." Mary, Jerry, and the pheasant farm ended up on land on the northwest edge of Miller.

Mary started out knowing nothing at all about raising pheasants, but learned quickly and gained experience. There was no shortage of things to do on the Seeman Pheasant Farm.

In the fall, breeding stock for the following year had to be selected. Typically about 65 hens were chosen, and along with the roosters, they needed to be cared for through the frigid South Dakota winter.

In the spring, the birds were put in pens with a ratio of six to nine hens to one rooster. Mary's pens had boards on the sides to prevent the roosters from seeing each other, keeping their minds on the task at hand rather than on fighting. In nature, hens lay their eggs in nests, but in captivity, they lay them on the ground, so the eggs needed to be collected frequently to keep them from being broken or eaten by the flock. Each hen lays 50-60 eggs during the spring and summer seasons, resulting in around 3500 eggs that needed to be collected; about half of these would end up hatching. Mary collected eggs at least once a day, and used a spoon secured to the end of a stick to avoid having to enter the pens and potentially upsetting the birds, resulting in broken eggs.

The eggs were placed in an incubator and later candled to determine which eggs were viable and which were not. The process of candling involves holding the egg in front of a bright light to see if there is an embryo forming inside. Mary would do this at night. Fertile eggs were put back in the incubator and the others discarded. The eggs would hatch after 23-24 days and the young chicks would be placed in the brooder house for 6 weeks.

The eggs were placed in an incubator and later candled to determine which eggs were viable and which were not. The process of candling involves holding the egg in front of a bright light to see if there is an embryo forming inside. Mary would do this at night. Fertile eggs were put back in the incubator and the others discarded. The eggs would hatch after 23-24 days and the young chicks would be placed in the brooder house for 6 weeks.

Mary's brooder setup consisted of an outbuilding with three rooms, separated by small doors only 4' tall, each room containing a heat lamp to keep the young chicks warm. Each brood of chicks was kept separately, as they would kill each other if mixed. After six weeks the chicks were moved to outdoor pens.

Pheasant pens, measuring about 72 x 125', housed the young chicks. Again, each brood was kept separately. She clipped their right wings to prevent them from flying out of the safety of their pens, and one by one clipped their upper beaks with fingernail clippers to keep them from pecking each other. Their diets were changed from a commercial feed ration to a growing mash with wheat screenings added to the mixture, which were obtained from the local elevator. Feed rations were adjusted during the summer months to bring the birds to their proper dressed weight of 3-4 pounds. Just before the start of the pheasant hunting season, which was when business peaked, the feed was changed yet again to fine-tune this process. Then, the dressing and freezing began.

So, while Mary initially got involved for "something to do," she ended up with plenty to do.

Pheasant pens, measuring about 72 x 125', housed the young chicks. Again, each brood was kept separately. She clipped their right wings to prevent them from flying out of the safety of their pens, and one by one clipped their upper beaks with fingernail clippers to keep them from pecking each other. Their diets were changed from a commercial feed ration to a growing mash with wheat screenings added to the mixture, which were obtained from the local elevator. Feed rations were adjusted during the summer months to bring the birds to their proper dressed weight of 3-4 pounds. Just before the start of the pheasant hunting season, which was when business peaked, the feed was changed yet again to fine-tune this process. Then, the dressing and freezing began.

So, while Mary initially got involved for "something to do," she ended up with plenty to do.

While the business was largely a success, not everything always went smoothly. One year a windstorm wiped out the entire flock. Neighborhood cats constantly preyed on the young chicks. Hawks and owls were a frequent threat. One particular owl kept killing Mary's birds, so she set a trap and when the perpetrator was caught, she called the Department of Game, Fish and Parks to come and get it. The officer did, but promptly turned it loose again and it came right back and continued to kill her birds. So she found a more permanent solution to the problem.

Ironically, pheasant hunters were Mary's best customers, even when they got their limit in the field. Her dressed, frozen pheasants did not count against their limit and frequently the out-of-state hunters gave away the birds they'd shot to local friends who could clean and dress them easier than they could.

|

| Mary's grandsons converge upon Hand County for some pheasant hunting. |

They turned to captive-raised pheasants, which were much easier to transport back home for their own dinner tables. Also these pheasants, Mary explained, tasted much better than their wild counterparts and there was no shot or broken bones to content with which made their wives happy while cooking them.

While most of her pheasants were sold "for the dinner table," Pheasants Unlimited, Inc. of Sioux Falls, also purchased birds to bolster the pheasant population in Hand County.

The department contacted Mary and asked if she might be able to help. Three hens and three roosters were donated from her flock. It was initially announced by the GF&P that they had caught these birds in the wild, but local newspapers called it "propaganda" and made sure the true story of the pheasants' origins was known. Regardless, Senator Mundt predicted, "It will probably pep up the old bird when it sees a real healthy, proud South Dakota pheasant," he said, "and it will start acting like one instead of like the pigeons with which it now apparently associates."

|

| Various newspaper clippings about Mary's pheasant farm |

|

| Some of the items Mary made with feathers collected from her flock |

During hunting season she had a window display in one of the shops in downtown Miller, and the items sold briskly with out-of-state hunters being anxious to return home with a gift for their wives or a remembrance for themselves.

Some of Mary's grandchildren were involved in the pheasant farm operations as well. In the winter, if snow was deep and the birds could not make it to their attached sheds for shelter, they'd huddle together under the snow, and the grandkids would have to get inside the pens and poke around for them. They could last awhile in these "snow caves," having both warmth and water in the form of snow but needed to have someone keep an eye out for this situation so they didn't starve.

Grandson Gary helped daily with whatever was needed - gathering eggs, hauling 5-gallon buckets of water, and helping catch birds and pluck feathers when it was time to dress the pheasants.

Though the Seeman Pheasant Farm is long gone, pheasants are never far from the hearts of Mary's family - from her sons, to her grandsons, and now her great-grandsons. Annually, they still gather for family hunting.

No comments:

Post a Comment