Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here, Part 6 here

To be continued...

Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here, Part 6 here

To be continued...

Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here, Part 6 here

1907 and 1908 were the years of change for Pete. In 1907 he traveled to California, planting seeds for what would later become a major change in direction, and in 1908 he went back to Denmark. Why he returned isn’t known, but when he re-entered the U.S. he was listed as a “non-immigrant alien.” He arrived back in Iowa in March. Sometime in this time period he met Clarence H. Bell, a bakery owner in Missouri Valley, Iowa. How they made their acquaintance isn’t apparent. Missouri Valley is about 25 miles from Council Bluffs. Bell, a 38-year-old business man teamed up with the 24-year-old baker and they went into business together. In 1908 they bought the City Bakery in Huron, South Dakota, a location neither man had ties to, but the City Bakery was a good acquisition after a number of failures for previous owners. Bell explained, “I first saw the town in 1908. I had come up to South Dakota from Missouri Valley, Iowa, where I had been in the bakery business for 10 years. I felt that this state showed great possibilities, so I looked several cities over and finally decided on Huron. Huron didn’t have a bakery then, and I knew I could make money there. It kept me hopping about 16 hours a day, and a half a day on Sunday.”

|

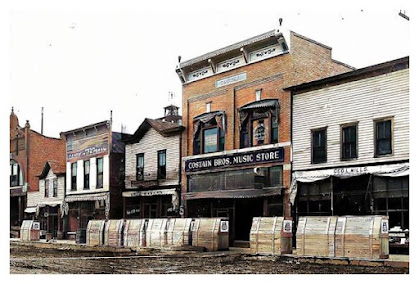

| Bell Bakery is the two-story wood frame building to the left of the large Costain Music Store. |

They purchased the bakery on September 23 and relocated to Huron immediately. The Bell Bakery was open for business by October 17, advertising that they took phone orders and made deliveries, and their products were already on store shelves. Bell ran the business and Pete produced the products. Together they were a profitable team. Pete had a good work ethic and was a hard worker. The products put out by Bell Bakery were high quality, and while there were other bakeries in town over the years, Bell Bakery had no real competition.

|

| The Bell Bakery delivery cart, about 1909 |

|

| The bakers: Pete Christensen is pictured 2nd from right, and his brother Soren is 3rd from right. Photo taken about 1911. |

|

| . |

|

| Above: The new I.O.O.F. building, with Bell Bakery on the main floor in the store front to the right. |

|

| The back room of the bakery. Pete is pictured at left. |

Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here, Part 6 here

|

| The S. S. New York |

It was April 20, 1901 when Pete boarded the ocean liner S. S. New York from Southampton, England. Southampton was a major, established point of departure for transatlantic voyages. At the time of this boat’s launch in 1893 it was called The City of New York and was the largest and fastest ocean liner crossing the Atlantic. The massive boat was 528 feet long and 63 feet wide and could accommodate 290 first-class, 250 second class, and 725 third-class passengers. This ship, in 1912, had the notoriety of nearly colliding with the Titanic on the latter ship’s maiden voyage departing Southampton.

Pete stepped foot on American soil on April 30 after a ten-day journey. He was 16 years and 11 months old, could read and write, and claimed “farmer” as vocation. His final destination was Exira, Iowa, where surprisingly his maternal grandfather, Peder C. Larsen lived. From there, he boarded a train for Iowa.

|

| Peder and Jacobine Larsen |

Pete’s grandparents, Peder and Jacobina Larsen, had immigrated between 1890 and 1895 in order to join the rest of their children - Soren, Niels, Anna and Kjersten - who had come to the United States about 1886. Their daughter Elsie, Pete’s mother, was the only one of their children opting to stay in Denmark.

It was said that Pete learned the baking trade from an uncle in Omaha, Nebraska, but there is no known uncle in Omaha at that particular time. Pete appears to have stayed in Exira until 1903, possibly helping out on his uncle and grandfather’s farm. In 1903, his older sister Katrina and her family immigrated and joined Pete in Exira. Katrina’s husband, Jens Jensen, was a baker in Denmark and established himself in that occupation in Council Bluffs, Iowa. About the same time, Pete also moved to Council Bluffs, where he learned the baking trade and worked for bakers in the city for the next four years. It is entirely possible that he apprenticed with his brother-in-law, Jens Jensen.

One by one, most of his siblings made their way to Iowa, several of them helped by Pete to immigrate, and he helped them get settled. His brother Chris and sister Katrina arrived in 1903; Laura in 1908; Caroline in 1909; Soren in 1910; and Martinas in 1911 and Mary sometime before 1919. Only Gjertrud stayed behind in Denmark.

Back in Denmark, Pete’s mother Elsie married Jens Eriksen, a neighbor 11 years her junior, and the two of them also immigrated in 1911, settling in Omaha, Nebraska, across the river from Council Bluffs.

To be continued...

|

| Laust/Lars & Elsie Christensen |

However, an article in the Dakota Huronite (Huron, SD) mentions his arrival in Beadle county in the March 08, 1883 edition. "H. D. Giard, Levi Giard, Adolph Giard and Dan'l Bottum, who with their families comprise a party of 13, have arrived in the city from Cohoes, N.Y. The gentlemen are all bright looking, energetic young men who appear to be firm in their determination to make their western venture a success. They cannot well help succeeding." Levi and Adolph are documented as brothers, and Daniel Bottom is the husband of their sister, so it's a reasonable assumption, barring the absence of any hard evidence, that Henry is a brother to Levi and Adolph.

Further circumstantial evidence is their choice of land. Adolph and Levi had cash purchase of land in Cornwall township, as did Henry. The location of their land, in relation to each other, also suggests a close family tie. Henry and his wife Alice homesteaded their land, and Alice "proved up" on the claim Dec. 13, 1889, as a widow.

The map above, shows the land of the Giards, NE of Hitchcock, South Dakota. The blue marker shows the location of Peck cemetery, and to the NE of that marker is where the Giard lands are located. The Green "L" is Levi's land; the blue "H" is Henry's land, and the red "A" is Adolph's land,In March, 1883, the brothers and their brother-in-law arrived in Dakota Territory. In July, 31 year old Henry was laid to rest in Peck cemetery. What, exactly, happened in those four months may be lost to history.

Henry and Alice had two children - Blanche, b. 1881 in New York, and Boyd, b. 1883. Alice appeared to have remarried William Goodman, and left South Dakota.

Way

out in the middle of nowhere, along South Dakota highway 28, sits a quiet

little unobtrusive cemetery. It’s something

you could drive by a million times and never realize it was there – unless you happened

to see the white sign saying, “Peck Cemetery - Dakota Territory” hanging from a

fencepost. Although the few remaining

stones are toppled and broken, someone neatly mows the final resting place of

these pioneers, all of them with their stories that have mostly been lost to

time. Most of the stones are unidentifiable,

but among them sits the grave of Mary A. Rounding, a young woman who left this

earth in 1883, far from her home.

Mary was the daughter of John and

Cynthia Rounding of Mount Carmel, Illinois.

Her father was in the service of the Union Army and died before his

daughter had even turned two years old.

A member of Company G, 41st Infantry, he fought in the

infamous Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee. This bloody, savage battle lasted two

days, hard fought by both sides. It was

an important victory for the Union as it allowed Ulysses S. Grant to penetrate

the interior of the South and make his way to Corinth, Mississippi. The wounded hero survived for a short time,

but sanitation was lacking and disease was rampant. Two weeks after the end of the battle, John

succumbed to his illness and wounds on April 20, 1862. His widow was left to raise their tiny

daughter without him. He was a

hero. But not the only hero in his

family.

Young Mary, the namesake of her

maternal grandmother, grew to young adulthood with her mother, stepfather, and seven

half-siblings. In the spring of 1882,

she left her family behind and accompanied her great-uncle, Capt. Samuel B.

Lingenfelter and his wife Mary Eliza to Altoona township, Dakota Territory. Mrs. Lingenfelter had several children, and

also was in the later stage of consumption so Mary’s presence was greatly needed

and valued.

On a stormy evening in August 1883

everything changed. A vicious cyclone

hit the Altoona area, destroying buildings, crops, livestock, and anything in

its path - which unfortunately included the Lingenfelter home. Mary shielded the children from flying debris

and hail the size of chicken eggs. While

trying to rescue them from the rubble, Mary sustained a serious spine injury and died less than a week later.

Mrs. Lingenfelter, who herself would pass away two months afterward, spoke

with the highest of praise for Mary. Heroism

must run in their family.

Out there in the middle of

nowhere, under a broken gravestone, lies Mary Rounding. She was a valiant soul who, like her father,

gave her all – her very life – for the good of others. Her story deserves to be heard and known and

remembered. SHE deserves to be known and

remembered.

The

window. The little window on the left,

with Grandma’s curtains still hanging nicely on either side of the sink.

I

never knew how much that window meant to me.

It was just a window. We came and

went from that house about a million times over the 33 years I spent with

her. And every time we left, there she

would be, at that window, waving as we left the driveway, from the time I was a child, through my adulthood and the lives of my children. She'd wave, and we’d wave back.

That

window had never looked so empty as it did the first time I left the house

after her death. There wasn’t just an

emptiness, but a cavern on the other side of that glass. For all the times I’d left the house and

waved on my way out of the driveway, I never realized the significance of that simple gesture, or the smile that accompanied it.

I’ll never see that sight in real life again, but I see it in my heart

every time I see that window.