On the corner of what was then First Street and Kansas avenue sat the Menzie House, one of Huron’s many early hotels. A two-and-a-half-story building, it also included a livery stable further down the street. Like other hotels in booming towns along the railroad, it saw its share of guests. And in the case of the Menzie House, it saw its share of trouble, too.

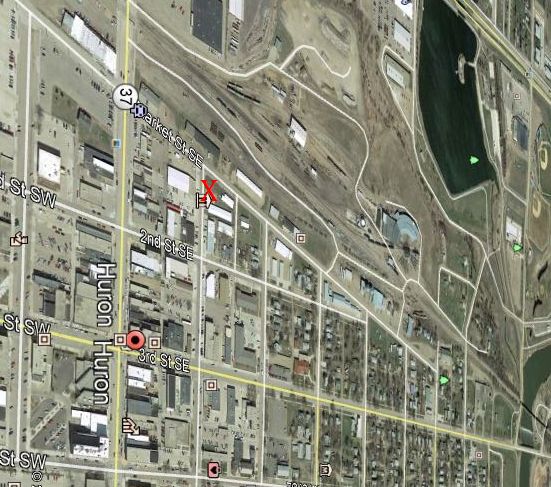

Above: The red "X" shows the location of the Menzie property, with the hotel to the left, and the livery stable to the right.

Below: the same area, with the red "X" marking the location of the hotel.

The hotel was opened by New York

native John W. Menzie in 1883, and was described in the local newspaper as “well-kept

and furnished, with large, bright rooms.”

Mr. Menzie, the article elaborated, “takes pains in making his house

inviting in its arrangements, its cleanliness and the splendid table regularly

set before his guests. As a host Mr.

Menzie has the happy faculty of making his guests feel at home, and pays strict

attention to the many details that help to make a hotel a success, and which

disregarded are sure to bring failure.” But, at some point details were indeed disregarded.

What brought the Menzie family to

Huron isn’t known, but their tenure in the town, and in the hotel business, was

about 10 years. And in that time, they

lost a barn to fire, a child to death, had another child abducted, had one

employee kill another, had a patron claim to be drugged and robbed, and another

patron died refusing to divulge his identity.

In addition, Mr. Menzie was arrested several times on charges relating

to his operation of the hotel.

Perhaps good help was hard to find

in those days. Or perhaps Mr. Menzie

wasn’t particular about his employees. It

was in August of 1886 that Menzie’s livery employee, Nathan Freeman, described

as easily angered, killed Joseph Kessler, another Menzie employee. Kessler, also described as “high-strung and quick-tempered,” was in

charge of the general operations at the hotel.

Kessler was critical of Freeman’s handling of the horses, and his expletive-laced

“suggestions” to Freeman were not well-received. An argument with “coarse words” and a scuffle

broke out, but they eventually separated with little physical harm done, except

for a scratch on Kessler’s face which infuriated him. Kessler made some threats, and threw a

punch. Freeman headed for the hotel building

to find Mr. Menzie, intending to resign, but by the time he got there he

decided to go home to have his mother sew his ripped shirt and return to his

duties in the livery. Before returning

to work, however, he grabbed a revolver and took it back to work with him. Back at the livery, witnesses say that

Kessler continued to harass Freeman, and Freeman could be heard telling

Kessler, “Don’t come near me – keep away from me!” But Kessler continued toward him, so Freeman

took out his gun and raised it to fire, but Kessler hit Freeman’s hand to try

to knock the gun from it, and it discharged, entering Kessler’s left

temple. He fell to his knees, then prone

to the floor. Dr. Huff did all he could

do, but the bullet was lodged deep in Kessler’s brain, and he never regained consciousness. He died a few hours later. Freeman was arrested for murder, but was

later acquitted of the charge.

The site of the old Menzie Livery, where Joseph Kessler was killed.

A few years later, the Menzie’s four-

year-old adopted daughter, Edith, was abducted. Mrs. Menzie had been out shopping, and

picked up a letter at the post office from the child’s birth mother, Ada

Hawthorn, telling her that she “need not be surprised should Edith disappear at

any time.” In fact she might be gone

before the letter even reached Mrs. Menzie.

Ms. Hawthorn clearly stated numerous reasons why the child should no longer remain in the Menzie family, but the primarly

reason was that the Menzie House was not a proper home for her. It was late in the afternoon when Mrs. Menzie

got the letter from the post office, and returning home, she began looking for

Edith, but no one had seen her “for some time.”

The police were summoned and felt confident that the child would be

found and returned, and apparently at some point in time she was indeed returned

to the Menzies.

In 1893 J. Rosenthal took over the Menzie

House and dubbed it “Hotel Columbia” and let the town know that it had been “thoroughly

cleaned and repaired, and will be kept in first-class order.” What, exactly, happened after that isn’t

clear, but it appears that John Menzie was back at the helm a short time after

that.

In January of 1895, Menzie House

was raided, and beer and other liquors were found. The house was closed “by injunction” and the

Menzie family was forced to find shelter elsewhere. The police had been watching the hotel for

some time and the local paper commented, “One would think that the frequency

with which Menzie and his establishment get into trouble that he would become

tired and cry ‘give us a rest.’” But

there was no rest. Menzie was arrested

at least once for selling liquor without a license, was fined at least twice

(and his wife and son each at least once) for “keeping a disreputable house.” After

his wife’s arrest, Menzie “sniffed trouble” and left town, despite having his

own similar charge pending in court.

Said the local newspaper, “Menzie left for parts unknown on a former

occasion and remained away from Huron for two or three years. The moral atmosphere of the town was not

improved by his return.”

The Menzies made their way to Indiana, where they opened a used furniture store in Muncie, and opened another "Menzie House" hotel in Matthews, as well as adopted another

daughter. By 1910, they had moved to

Ashtabula county, Ohio, where Mr. Menzie died in 1922.

| The current site of the old Menzie House hotel, on the corner of what is now Market Road and Kansas ave. |

By 1896, the hotel building in Huron was owned

by Richards Trust Company, and the business was being advertised for rent with

the statement, “A good chance for a good man.”

By 1898 it briefly housed the “Farmers Home” and in 1899 was

purchased by James McWeeny and dubbed the “McWeeny House.”

Sources:

Sanford Fire Insurance Map of Huron, South Dakota 1884 - 1898

The Daily Huronite – numerous issues from 1885 - 1936

Sioux Falls Argus Leader - Nov. 19, 1890; Jan. 5, 1895; Jan. 26, 1895;

March 13, 1895.

1900, 1910, 1920 Federal Censuses

Muncie, Indiana City Directory 1899-1900

The Star Press, Muncie, Indiana, Aug. 28, 1905

“Huron Revisited”

Google Earth